The consulting firm Brad Taylor works for, JCK Engineering, did work on the College Avenue Campus Renewal Project. That project involved renovating the entire College Building and Tower, restoring the façade, and constructing two new structures on either end to fit the functional needs of the university. Photo courtesy JCK Engineering.

The buildings that are restored are a physical representation of the decisions, aesthetics and efforts of those who came before us. To study history is to study change over time.

Brad Taylor, P.Eng., did not study history to become an engineer. He developed his technical knowledge and skills. But by working on projects that required he apply those skills in order for historic buildings to be restored, he has learned more about Saskatchewan’s history.

His assessments have shown him first-hand the changes in how buildings were designed, constructed and renovated in this province during its earlier decades.

In the beginning

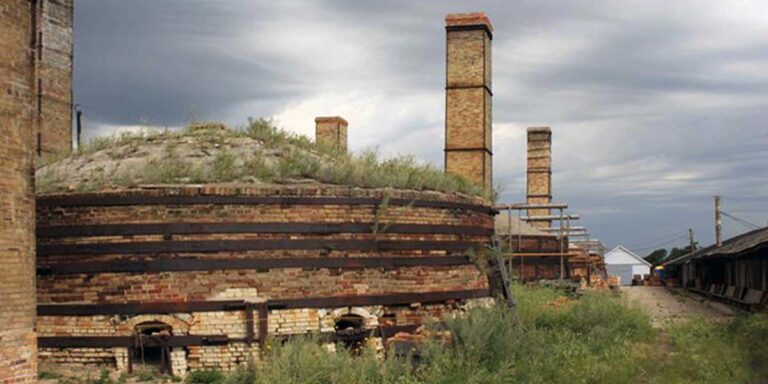

Taylor’s career as a structural engineer began with a project that would help to preserve Canadian history here in Saskatchewan. When he started at JCK Engineering as a junior engineer around 12 years ago, he was asked to work on its project at the Claybank Brick Plant National Historic Site. The site features a brick factory built in 1912 that allows visitors to appreciate an example of 20th-century industrial activity in Canada.

“I was specifically looking at the kilns, which include these really interesting dome structures,” said Taylor.

“I met with one of the masons who had worked there in the past to understand how they how they built them, their methods, and the different materials that they were using.”

“There are so many stories around Claybank that tell the story of southern Saskatchewan and tell the story of Saskatchewan’s impact on the world. There’s brick that’s been used around the world from that factory.”

Some of those structures built with Claybank bricks include the Chateau Frontenac in Quebec City and the rocket launch pads at Cape Canaveral. Other bricks from this factory were used to line the fire boxes of CN and CP Rail locomotives as well as warships in Second World War.

From that project, he has moved on to be a part of numerous other projects restoring buildings that tell the story of Saskatchewan’s earlier years as well as what is valued today, including Saskatchewan’s Legislative building and the College Avenue Campus Renewal Project in Regina as well as the Yorkton Heritage Flour Mill.

When Brad Taylor began his career as a junior structural engineer with JCK Engineering around 12 years ago, he was asked to work on its project at the Claybank Brick Plant National Historic Site. Photo courtesy Brad Taylor, P.Eng.

When Brad Taylor began his career as a junior structural engineer with JCK Engineering around 12 years ago, he was asked to work on its project at the Claybank Brick Plant National Historic Site. Photo courtesy Brad Taylor, P.Eng.

Engineering and structures

Changes happen to buildings over time, in part, because of the forces that act on them. Taylor assesses buildings with an understanding of those forces, known as loads.

“Structural engineers are concerned with, essentially, taking the gravity loads and the lateral loads from wind down to the ground,” said Taylor.

“We have to determine the loads and then we have to make sure that the materials that we’re relying on to transfer them down to the ground have enough strength and stability to do that.”

Building loads include the self-weight of the structure, architectural finishes and the equipment. External loads include snow, water, wind and seismic loads that contribute to the stresses and deflection in the building.

Taylor assesses buildings to find out how they are holding up. In some ways, he sees similarities between his job and that of a physician. Someone responsible for an older building comes to him with issues the structure is experiencing, similar to a patient describing their symptoms to a physician.

“People will often call us when they see indications of movement or some cracks. Maybe a wall or column is leaning or there are noticeable deflections, which raises some flag in their mind,” said Taylor.

“They know that they have some sort of issue here, but they don’t know exactly what they’re dealing with.”

Assessing a historic building

Taylor uses his technical knowledge and skill to come up with a determination of what is occurring and how to address it. He does so by starting with the foundation of the building.

“In some instances, we will excavate around portions for the building to expose the foundations. We take core samples to determine the strength and durability of the concrete, or in some cases, brick,” said Taylor. While assessing the foundation, he can see how, in decades past, there wasn’t always a full appreciation for the type of soil found in the Regina area, where a number of restoration projects require underpinning (or strengthening) the foundation or repairing it to ensure the building is stable.

Some of those doing the designing and constructing of Saskatchewan’s early buildings had come to the province from Eastern Canada or Europe, bringing with them methods that worked where they were from.

“We find often that some of those methods don’t really suit our soil conditions,” said Taylor.

He has worked on some stone and masonry churches that he found were built on very shallow foundations.

“Stone or masonry buildings with shallow foundations constructed on clay do not perform well in our environment,” said Taylor, which causes walls to move so they lean or crack.

Once the foundation has been assessed, he looks for water infiltration in the roof or the other parts of the building envelope.

“Moisture inside of wall cavities, especially masonry, are going to cause damage relatively quickly,” said Taylor.

The next step is to look for indications there has been movement in the building, such as deflection in the floors or leaning walls or columns. The assessment can also include testing the materials used in the construction of the building to determine their strengths while also ascertaining the actual loads to be applied to them to ensure the materials can handle them.

The safety of the building is affected by these factors. This structural safety is just one of the core objectives of the National Building Code, which Saskatchewan has adopted as the minimum standard for the construction and renovation of buildings throughout the province.

However, there was not a building code in place when some of Saskatchewan’s earliest buildings were constructed. Some of the construction he reviews was done based on best practices passed down from one generation to the next rather than regulated minimum requirements. (Although, to a degree, some of these best practices have been included in building codes.)

Change over time

Then, there are buildings that have been renovated through various eras, which may have included changes that do not complement earlier construction. For example, wall assemblies have changed over time. Early masonry wall assemblies had very little insulation and did not include a vapour barrier. Air and moisture could move through the wall assembly, which, in some instances, improved the durability of the wall.

Some renovations of historic masonry buildings included the addition of more insulation and a vapour barrier. This may have improved the energy efficiency of the building, but restricting the flow of air through the masonry can cause other problems. Freeze-thaw damage can cause the masonry to deteriorate and connectors within the assembly may be more susceptible to corrosion.

Assessing work done in the past has taught him something important about humans. Some hold the opinion that work done by earlier generations is superior to what is being done by people today, but Taylor sees it differently as he collects examples of issues he’s encountered in older buildings. Masonry provides some of those examples.

‘When you start digging into these buildings, you do find areas where adjustments had to be made because something was not constructed level or straight,’ said Taylor.

“But they were not perfect either.

“There are masons today that are just as skilled and committed to quality workmanship as there were 100 years ago, and to some degree, the craftsman who are restoring these buildings require even greater skill.”

Working with clients

Deciding whether a building be demolished or restored is not a decision Taylor makes. That is the decision of the client, who has to decide if the building meets their strategic needs and fits within their budget.

“Often, we just say this is what you need to do and this is approximately what it’ll cost,” said Taylor.

“We’re just giving people the technical information so that they can make an informed decision.

“It is important that owners have a full understanding of a building’s condition so that they can make an informed decision and not run into surprises if they choose to restore a building.”

Combining old and new

Sometimes, the entire building can’t be restored, but a portion of it that has historic significance can be incorporated into new construction. That was the case with College Avenue Campus Renewal Project, which involved renovating the entire College Building and Tower, restoring the façade, and constructing two new structures on either end to fit the functional needs of the university.

“Façade retention projects are super interesting,” said Taylor.

“At the College Avenue Campus, we had this three-storey wall that had to be temporarily supported while the building behind it was demolished,” said Taylor.

Then the new building was constructed and tied into the façade.

“While it was temporarily supported, there were new foundations added below the façade, which include small excavations and working under the footings of the original building.”

Then there were modifications to the tower that included the of two large passageways through 51-inch-thick masonry walls, which carries “an incredible load.” New beams and columns were designed in such a way that allowed the openings to be constructed through the loaded walls.

“That’s very stressful work. It takes really good relationships with the tradespeople you are working with,” said Taylor.

Photo courtesy Allen Lefebvre

Photo courtesy Allen Lefebvre

Building relationships

“That’s a great thing we have in Saskatchewan with a lot of our tradespeople. They have a mindset of working together with the owners and the engineers.

“We have really good relationships in the industry, too, with people that we trust and know that are going to do great work and are there to work with us. I know that’s a very important part of our success as a company.”

The importance of relationships in Saskatchewan is evident to Taylor and, through those relationships, he has recognized why people choose to spend on restorations, if they can acquire the necessary funds, through grants for heritage properties as well as other means, including fundraising.

His interactions with clients as well as with those he served alongside as a board member for Heritage Saskatchewan (where he was the only engineer) have helped him develop an appreciation for what these historic buildings symbolize.

“You learn about things that just blow your mind about how people survived in Saskatchewan and how they worked,” said Taylor.

“Most of the historic projects that we see are a testament to the hard-working spirit of people in Saskatchewan.”

The buildings that are restored are a physical representation of the decisions, aesthetics and efforts of those who came before us.

“These buildings are a part of who we are and that, I think, influences how we move forward,” said Taylor.

Brad Taylor, P.Eng.

Brad Taylor, P.Eng.

“Historic buildings add to the beauty of our cities, towns, and landscapes. We would not be better off without them.”